‘Edge of an Era: Performance, Then and Now’

Eleanor Roberts

Ulrike Rosenbach, videostill of ‘Dance in a madhouse’, 1988. Courtesy of the Artist. Courtesy of the Artist

The Guardian’s ‘Pick of the Week’ for 12 September 1988 tells us that

Performance art has never had a high profile in Britain, and there has been little cross-fertilisation between the UK and the rest of the world. In a crusade to change this Rob La Frenais, founder of Performance Magazine, has organised Britain’s first international performance art biennale.[1]

This assertion is to some extent wrong in that it elides histories in which UK artists had in fact toured, and were in conversation with international artists in and touring to Britain. However, it does concisely represent valid concerns about a geographically isolated (and historically imperialist) island, and a formal practice of making art which was and continues to be engaged in a struggle against the established or assumed terms of ‘high profile’ art. The event that the article refers to, EDGE 88 (13 – 25 September, 1988) was an art festival with a focus on site-specific performance and installation that took place at various locations around the Clerkenwell area of London.[2] It was organised by the founding editor of Performance Magazine Rob La Frenais,[3] Sara Selwood who was then director of AIR Gallery,[4] and co-ordinated by Alison Ely in collaboration with Projects UK, Newcastle. Its aim was to ‘bring experimental art to Britain from around the world, in particular live art’ while also ‘exposing and promoting innovative British art, which is currently unfairly isolated through lack of contact with foreign work’.[5] It was designed as an event which was to be closely intertwined and embedded within the local community of Clerkenwell, which had been considered by some a run-down area with many vacated industrial buildings at the time, in the midst of gentrification (a point that I will return to).[6]

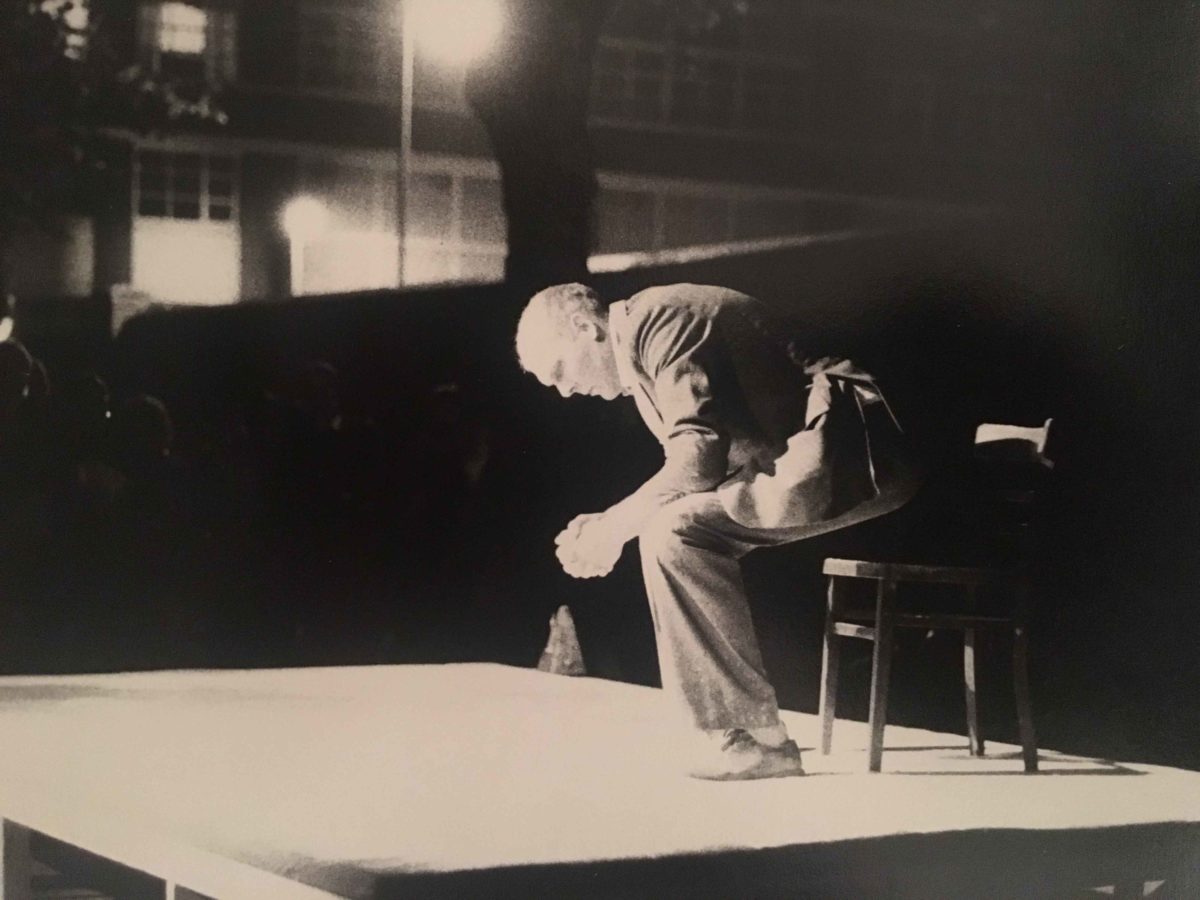

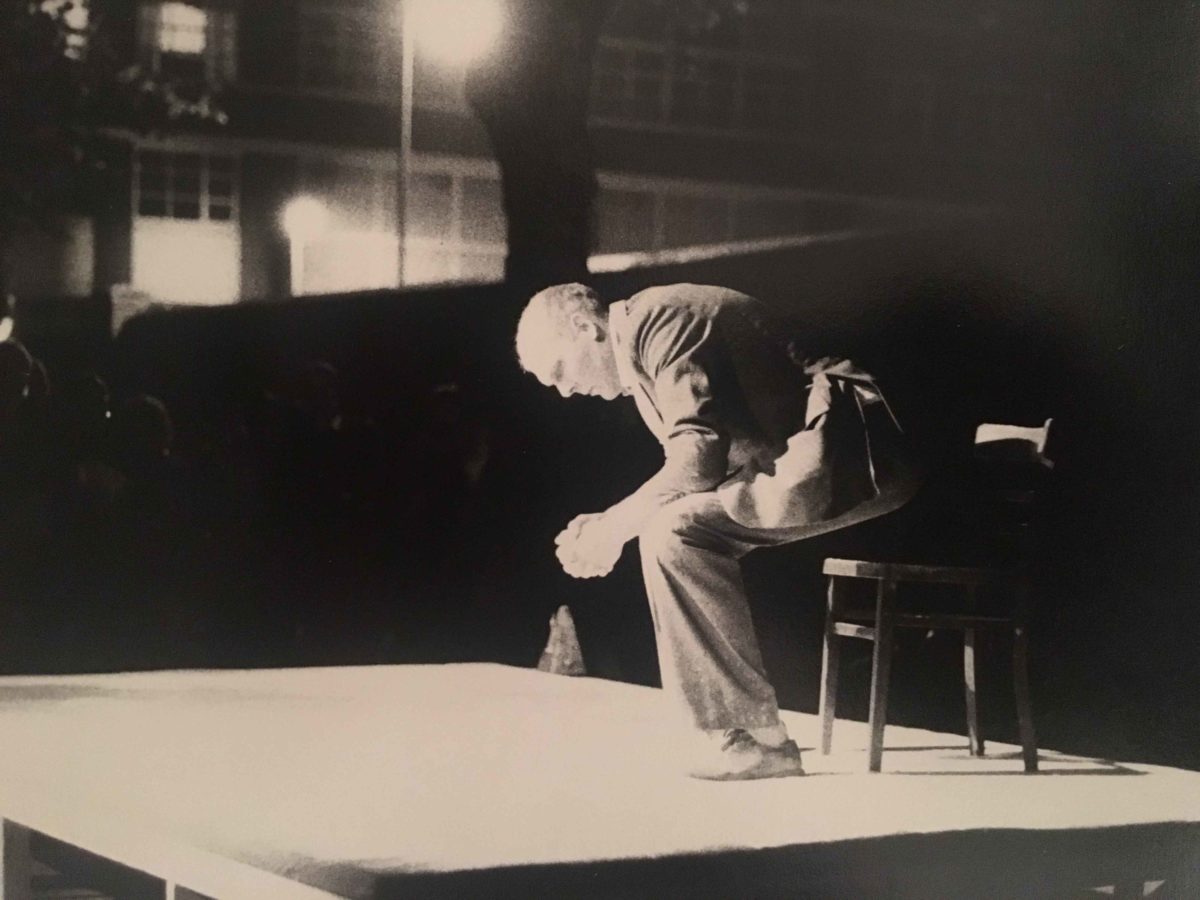

Nigel Rolfe, ‘Shooting Shitting’, 1988. Courtesy of AIR Gallery/SPACE archive. Courtesy of AIR Gallery/SPACE archive

The organisers saw experimental contemporary art, and live art in particular in terms of its potentiality, to counter deadening effects of the art market and its fixed objects, as well as staid institutions and their exclusionary or imperialist bases. A press release from the archive reads:

EDGE 88’s policy is implicit in its title. EDGE 88 and its collaborators believe that the process-based approach of many live and other experimental artists runs counter to the monumental and commodity based approach of traditional artforms, and that this approach knows no physical frontiers, either by media or national boundary.[7]

Indeed, the title EDGE situates the events in terms of innovation (the obvious ‘cutting edge’) and provocation (‘edginess’), but also in complex and not necessarily obvious ways it speaks to the politics of the marginal, the peripheral, or the extreme; it recalls a moment in time which anticipates or is a prelude to a possibility or change which is about to be realised (to be ‘on the edge’ of something); it is a position of precarity (on a knife’s edge); and tense or purposeful energy or movement (to be ‘on edge’, to ‘edge closer’). It speaks to the politics of EDGE 88 as a wilfully shifting point of concentration for itinerant art practices, also shared by other EDGE and related events, including the earlier Art in Danger (Diorama, 1985-86), At the Edge (AIR Gallery, 1987), Last Sweat of Youth (AIR Gallery, 1988), and subsequent events EDGE 89, 90 and 92, until the project’s end after a brief but impactful burst of activity that had taken place in London, Newcastle, Glasgow and Madrid. These events galvanised a set of practices in performance, installation, and otherwise time-based art, and represent a significant focus point in the history of live art in the UK and internationally.[8] It placed a diverse range of artists in conversation with one another: in EDGE 88 artists of the Black British art movement Rasheed Araeen and Mona Hatoum were situated in conversation with artists of colour internationally such as Chinese Canadian Paul Wong; works by feminist artists from the UK such as Helen Chadwick, Rose Garrard, and Tina Keane were placed alongside contributions by European and US artists Ulrike Rosenbach and Carolee Schneemann;[9] performances by Alastair MacLennan and Nigel Rolfe spoke to the urgent politics of the Irish Troubles; while Stuart Brisley, Ian Breakwell, Vera Frenkel, and Zbigniew Warpechowski were among those who represented the dismantling of art’s formal and disciplinary barriers and boundaries that unfolded in the 1970s and beyond.[10] A visitor’s experience of EDGE 88 began with a map and an invitation: to navigate thirteen sites including formerly industrial buildings, a public swimming pool, the cloister garden at the Grand Priory Church of the Order of St John, Finsbury Town Hall, and contemporary art spaces such as the Flaxman and Slaughterhouse galleries (spaces that are now gone), among others. Works in performance, sculpture, and installation were part of a programme which also included a conference and performance-lectures focused on questions of participation and international histories of art, which emphasised the sense in which art unfolds within, between and across discursive as well as physical spaces.[11]

Denis Masi, ‘Screen’, 1988. St James Church, Clerkenwell, London. Courtesy of the Artist

It is a good time to revisit these events, to take stock of the development of live and time-based art, but also the broader questions that EDGE touches on: issues of innovation, diversity, visibility, change, and the politics of place and space, to name a few. Thirty years after EDGE 88, on 4 February 2019 the Edge of an Era event took place at and around St. James Church, Clerkenwell as part of the broader project to document and respond to this history and live art of the 1980s. The project is led by the artist Helena Goldwater, Rob La Frenais, and Alex Eisenberg in collaboration with the Live Art Development Agency. The event began with two walking tours, one of which was led by La Frenais, who narrated EDGE 88 sites around Clerkenwell and remembered the works installed therein. Shortly after embarking on the journey it was clear to the tour group that it would not be straightforward to begin to reconstruct this history, as the majority of the sites had been privatised, built upon, or otherwise closed to public access or viewing. La Frenais commented while looking up at the site of formerly affordable artists’ studios on Clerkenwell Close: ‘artists can’t even afford to buy a pint here [now], let alone have a studio’, and perhaps expectedly the group was asked by a security guard to quickly move away from an area now converted to expensive gated flats. Standing in the street looking in the semi-dark at a high brick wall we nonetheless began to imagine, with Alastair MacLennan’s recollection of the subterranean Clerkenwell Catacombs (a remainder of Middlesex House of Detention), where his performance Bled Edge took place. MacLennan’s piece consisted of a 111 hour installation and performance which was about, MacLennan told us, ‘articulating and accentuating’ the existing aura of the space, where Fenians created a deadly gunpowder explosion in an attempt to free Irish prisoners awaiting trial in the 1860s, and where children had also been held as prisoners. Archival footage of the work shows MacLennan as a shadowy figure moving around a space littered with broken and ghostly objects such as smashed up wood, seemingly abandoned clothes, and British and Irish flags hanging from barbed wire stretching across heavy (and, in a way, sinister) old doors. The proposal for the piece speaks of ‘issues of political, social, cultural alienation and integration’, and MacLennan wrote, ‘When disaster strikes, do we wash the blood, heal the victim, or polish the floor? To heal we make WHOLE’,[12] which recalls – sadly and poignantly – histories of colonial violence, the Irish Troubles of the period, and also the threat to peace posed by Brexit today.

Later, at the Ironmonger Row Swimming Baths we were able to peek in through a newly built viewing window to the pool (in full public use) where Tina Keane’s The Diver took place. The work involved women diving and performing synchronised swimming, lit by a spotlight that followed them around the water that was otherwise in darkness. Footage of the work shows a woman playing a violin, the sound of which echoes around the pool as she floats on the water in an inflatable chair; later, another person dressed in a tuxedo jumps into the water as a deep and rumbling soundscape is heard. These strange and peculiarly ordered images are discordant with the usually very brightly lit and cacophonic space of a public swimming pool, and prompt a re-thinking or re-imagining of space and everyday life. Outside Woodbridge Chapel (Clerkenwell Medical Mission) we were told of Helen Chadwick’s Blood Hyphen, an ‘ambitious’ work of art responding to scientific research, La Frenais said, in which audiences had to climb some stairs and put their heads up into an opening in the ceiling of the chapel, at which point they could see a separate space above which was theatrically animated by a red laser and smoke. Chadwick’s proposal shows that the work was inspired in part by theological scholarship which had interpreted Jesus Christ’s wounds and blood in terms of maternal corporeality, and NHS information pamphlets on smear tests and cervical laser treatment.[13] Extant footage of the work shows the discovery of an alternate world above the chapel ceiling, centred on a previously hidden window drenched in red light to create a fleshy, translucent membrane in a womb-like space. In the archival footage Chadwick’s work contrasts with the bright sunlight and colours of the secret garden where Ulrike Rosenbach swirled around like a Whirling Dervish in her performance In the House of Women, a site which the tour group also caught a glimpse of through a closed gate.

As not only a backdrop, but in a sense an active agent in these works, the environment of Clerkenwell is now known as an area for architects’ offices and luxury furniture design shops; it is one part of vast swathes of the city that have been virtually vacated by communities as privatisation and the cost of living has risen exponentially. The sense of what is or could be possible for art in London has certainly changed, and perhaps in some respects even diminished. Archival photographs show Roberto Taroni in a local classroom preparing for his work Portrait de L’Artiste en Saltimbanque which called for fifteen young children to devise aspects of the performance, and to read a complicated text about ‘theory of dis-architecture’ (the reading of these phrases, which children were unlikely to understand, was pitched to them as a ‘game’) among other things.[14] During the tour Mona Hatoum recounted of her work, Reflections on Value which was installed at 8 Northburgh Street (a formerly industrial building) that she had appropriated found materials nearby which she used as part of her earlier installation Hidden From Prying Eyes (At The Edge, AIR Gallery, 1987), with La Frenais featuring in the story as curator turned getaway van driver. As corporate control over the city has become tighter (evidenced by the criminalisation of squatting and shrinking of public space, for example) it is more difficult to imagine such acts of appropriation being successfully carried out today. Yet, today’s Edge of an Era project is not one which is seeking to nostalgically reconstruct a past history. Rather, it is concerned with the idea of challenging and extending the archive with new acts of creation, connecting past, present and future with a sense of possibility, and with charting ways forwards while also reflecting on works already carried out. With this in mind, Goldwater, La Frenais, Eisenberg and Live Art Development Agency commissioned five emerging artists: Robin Bale, Zvikomborero (Mayfly) Mutyambizi, the collective Something Other (Maddy Costa, Diana Damian Martin and Mary Paterson), Adam Patterson, and Morgan Quaintance to create new works that are somehow in conversation with those of EDGE and its archival representation. Some of this work was represented at the evening of performances and a panel that took place at St James Church after the walking tours.

Walking Salon by Something Other (Mary Patterson and Diana Damian Martin). Part of Edge of an Era event, 2019. Photo: Christa Holka

In her introduction to the evening, Goldwater spoke of the impetus behind Edge of an Era, which was prompted by her frustration that she could not readily find or access materials on performance art events that had been influential to her as an art student in the late 1980s. Later on in the evening, Selwood provided some context for the organisation of EDGE 88, and commented on its demanding responses to ‘raw’ spaces yet to be gentrified, as well as the effects of damaging political changes instituted by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, who had then been in power for almost a decade. La Frenais emphasised historical (and, implicitly, contemporary) concerns about how to create opportunities for international exchange between artists in the face of limiting funding structures; particularly, he addressed the restrictions at the time on the Arts Council funding international work, and that EDGE precipitated or contributed to a change in policy. In his contribution to the panel discussion Alastair MacLennan revisited the function of live art itself, which he characterised in terms of a sense of connection between people as well as times, places and things. These concerns with the formal and political opportunities presented by performance were well represented and responded to in the new commissions. As part of the evening, Something Other (who had also given their own walking tour which explored women artists’ proposals and performance sites) presented work from their Archives of Now, which centred on feminist notions of correspondence between women across time and space. The work culminated in a series of audio letters which speak to (and, in strange ways, from) the women artists of EDGE 88. As the audience were seated, three voices (those of Johanna Linsley, Nisha Ramayya, and Diana Damian Martin) cut across the space from different angles above and around the church pews. They spoke of the fragility of the past as evidenced in the archive, fragmentary and peripheral documents replete with errors, temporal migrations and wanderings, being lost, recalcitrance, and the market’s undue influence on history. The text is comprised of snatches of scenes or ideas such as ‘have you given yourself permission to steal or destroy?’, ‘it’s always hard to be a woman’ (which seems at the crossroads of irony and seriousness), and references to digitally stored records or memories ‘reaching out an invitation, across the warm stretch of time’. Fittingly, the letters begin ‘to you’ and end ‘with love’, which foregrounds their function as correspondence between women, as they reach towards a transgenerational current, conversation, or exchange.

Adam Patterson – ‘Looking for Looking for Langston’, performance. Photo: Christa Holka

Next Adam Patterson, a Barbadian artist based in London and Rotterdam, represented his work Looking for Looking for Langston, which was created in response to Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston, shown at EDGE 89 in Kings Cross in the abandoned wastelands that would become the site for the new Central Saint Martins College of Art, and EDGE 90 in Newcastle. Julien’s piece, which is primarily known as a film work, was inspired by the Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes; as Patterson looked at Julien looking at Hughes, he sustained and extended a thread of connection that spans a century, punctuated by acts of contemplation and desire between black artists. In St. James Church, Patterson walked from behind and through the audience and looked at the screen above which showed a new video rendering of Julien’s Langston on a Caribbean beach. Standing with his back to the audience Patterson wore a white, textured avant-garde costume that was part naval officer, part feathered cockatoo, and part gold glitter bomb. Tiny bells on his tall, fluffy hat tinkled to accentuate moments in a text spoken to the image projected above; Patterson began with a scene of togetherness, eroticism, and fantasy set in a sea shell: ‘We speak and kiss in conch, its inner ear a passage to our “elsewhere”’. Patterson’s figure made for a fantastical and exotic bird which seemed at odds with the tall coldness of the church and its dull colours, perhaps speaking to the exoticisation and Othering of black bodies in cultural and historical institutions in the UK.

Travels and wanderings between times and generations were also marked by Morgan Quaintance, in a video work Anne, Richard & Paul which sutures archival and new footage of Bow Gamelan Ensemble members (who were part of At the Edge, 1987),[15] and Robin Bale who closed the evening with a response to Alastair MacLennan’s EDGE 88 work. In his performance, Invocation, Bale stood on a balcony above and behind the audience, creating a soundscape with a drum, electronic noise, and a spoken text which included statements that destabilise the archive, such as ‘I wasn’t there’ and ‘it never happened’.[16]

Video still from ‘Anne Richard and Paul’, by Morgan Quaintance, 2018

Centred on the notion of inter- or transgenerational exchange, the Edge of an Era event marked the fact that many questions raised by the proliferation of performance in the 1970s, the 1980s (and before and beyond) remain perennially and actively unresolved. During the discussion, one audience member reaffirmed the established notion that artists working in performance have resisted documentation and – going further still – suggested that some may not wish to even be remembered. Indeed, recent events which have sought to reappraise histories of performance have sometimes had an undercurrent of fraught energy, as the interpretation (or neglecting) of an art work by audiences may clash with the wishes of artists who may not agree with how their work is received, and (importantly) the negotiation becomes more complex when the work represents or seems to ontologically overlap with the artist’s body or sense of self. Another member of the audience repeatedly objected to the use of the word ‘important’ during the panel discussion. As this person did not elaborate on the reasons behind their objection, one can assume they were speaking to live art as a form which has been (actively, critically, generatively) frivolous or ridiculous, seemingly fleeting, and which has countered the terms of institutional ‘importance’. Indeed, during the panel archival footage of EDGE 88 was projected onto a screen above, and while speakers were discussing the festival’s organisation and issues of funding, the video behind (unbeknownst to them) showed a close up of Polish artist Jerzy Bereś’s cock and balls, as he painted the end of his penis to mark the dot of a white question mark he had painted onto his naked torso – a pleasingly absurd juxtaposition that dissipated conventional notions of seriousness. While acknowledging the aforementioned political impetus and history of live art, I want to counter that audience member’s objections and make a case here for the importance of these events. The original EDGE events and Edge of an Era advocate for intergenerational exchange, internationalism, diversity, site specificity, community, and visibility for artists and art movements frequently written out of historical record. At a moment in time in which artificial national borders are being hardened, in which the migration of people is curtailed and criminalised, gentrification empties urban neighbourhoods of communities and their cultures, and institutions (which are often neglectful of, or indifferent to, live art) are calcified by corporate concerns, it is far more strategic to insist on the importance of these achievements and collaborations past and present, which open up alternative methods, sites and routes for navigating art’s future.

Dr ELEANOR ROBERTS is a Lecturer in the Department of Drama, Theatre & Performance at University of Roehampton. Her research to date has been concerned with feminist historiographies and archival studies of performance, including performance art of the 1960s and 1970s, and the politics of visibility. This includes ‘Live Art, Feminism and the Archive’, a collaboration with Prof. Lois Weaver and Live Art Development Agency (LADA) that sought to map and respond to feminist histories of performance. It involved creating a forum for conversation about live art and contemporary gender politics for women and queer artists across generations, and culminated in a print and online publication Are We There Yet? – A Study Room Guide on Live Art and Feminism (2015). She has also collaborated with LADA on Live Art and Feminism in the UK, an online Google Cultural Institute exhibition. Her research has been published in Contemporary Theatre Review and Oxford Art Journal.

Credits

This essay was commissioned as part of Edge of an Era, 2018. Edge of an Era is curated by Helena Goldwater and Rob La Frenais, Alex Eisenberg and Live Art Development Agency, London. Supported using public funding by Arts Council National Lottery Project Grants with additional activities made possible through the Jonathan Ruffer Curatorial Grant from Art Fund.

www.edgeofanera.co.uk

Endnotes

[1] Claudia Stumpfl, ‘Pick of the Week: In Performance’, Guardian, 12 September 1988, clipping Edge of an Era archive, http://www.edgeofanera.co.uk/archive.

[2] In this essay I refer to ‘performance’, ‘performance art’, and ‘live art’, all terms with different implications and histories in terms of their usage. For instance, ‘performance art’ can be considered a pre-history of ‘live art’, as the former has been used in relation to the proliferation of performance in visual art contexts in the 1970s, while the latter first emerged in the late 1970s but did not come to define or galvanise a set of interdisciplinary performance practices until the later 1980s and 1990s onwards – particularly in the UK. While the organisers of EDGE 88 use the term ‘live art’ throughout their press release and other papers, the newspaper coverage and other critical responses refer to ‘performance art’ (as perhaps a more well-known term). Indeed, contributors of Edge of an Era see these terms differently; for instance, Helena Goldwater refers to ‘performance art’ as the term that best reflects the discursive framework understood in and around art schools in the late 1980s, while Alastair MacLennan referred to ‘live art’ throughout his panel discussion which reflected on EDGE 88. In this essay my usage of the terms therefore changes in accordance with how different people represent themselves, and I use ‘performance’ as a more general umbrella term which refers to art work centred on live human action. This invokes the larger discussion about how practices denoted by live art have often been written out of historical record in favour of more institutionally visible or museologically amenable practices (often represented as being within the framework of performance art), but there is not the space to discuss this here.

[3] Performance Magazine was a publication about contemporary interdisciplinary art, and which eventually came to be focused on live art; it ran from 1979 to 1992, initially on a mostly bimonthly issue basis. See, http://www.performancemagazine.co.uk/.

[4] AIR Gallery was an artist-led information hub and gallery space for contemporary art particularly active in the 1970s and 1980s. AIR (Art Information Registry) was founded by the artist Peter Sedgley as an artist-led co-operative in 1968. It was linked to another initiative, SPACE (Space Provision Artistic Cultural and Educational). While AIR did not initially have a physical, publically accessible home, AIR Gallery was subsequently established and existed at a number of central London locations. It was known for innovative art and performance practice, artist-led initiatives at intersections of art and activism, and showed work by women and BAME artists such as Sonia Boyce, David Medalla, and Carlyle Reedy among many others. See, John A. Walker, Left Shift: Radical Art in 1970s Britain (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2002), pp. 139, 209, 217-8.

[5] EDGE 88 Press Release, Edge of an Era archive, http://www.edgeofanera.co.uk/archive/.

[6] AIR Gallery, ‘Callout Locals Volunteers, 1988’, Edge of an Era archive, http://www.edgeofanera.co.uk/archive/.

[7] EDGE 88 Press Release, Edge of an Era archive, http://www.edgeofanera.co.uk/archive/.

[8] Other points of focus for performance and live art in the UK named during the evening were the London Calling festivals (Acme Gallery, 1976 and 1978), Nikki Millican’s initiatives New Moves and the National Review of Live Art (the latter ran as a festival from 1986 to 2010, with roots in events since 1979), and the Live Arts programme at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts [ICA] when Lois Keidan and Catherine Ugwu were directors between 1992 and 1997.

[9] I note here for historical record that while VALIE EXPORT was scheduled to attend and appears in the catalogue, she was in fact unable to attend EDGE 88 due to ill health. Rob La Frenais, correspondence to the author, 9 February 2019.

[10] While I am categorising these discursive areas here to give a sense of the event overall, these categories are of course artificial as the artists moved across and between overlapping, inter-connected, and concurrent movements and spaces.

[11] For a more detailed description of a range of the EDGE 88 events see Stephen Durland, ‘Throwing a Hot Coal in a Bathtub: London’s EDGE 88’, High Performance, 44 (1988), 32-41.

[12] Alastair MacLennan, Bled Edge proposal, Edge of an Era archive, http://www.edgeofanera.co.uk/archive/.

[13] Helen Chadwick Blood Hyphen proposal, Edge of an Era archive, http://www.edgeofanera.co.uk/archive/.

[14] Roberto Taroni, Portrait de L’Artiste en Saltimbanque, image documentation and text, Edge of an Era archive, http://www.edgeofanera.co.uk/archive/.

[15] The Bow Gamelan Ensemble were an experimental art and music group focused on site-specific situations, creating new musical instruments out of found materials, and improvisation; its members were Anne Bean, Richard Wilson and Paul Burwell.

[16] The commission by Zvikomborero (Mayfly) Mutyambizi was unfortunately not available for viewing at the Edge of an Era event.

‘Edge of an Era: Performance, Then and Now’

Eleanor Roberts

Ulrike Rosenbach, videostill of ‘Dance in a madhouse’, 1988. Courtesy of the Artist. Courtesy of the Artist

The Guardian’s ‘Pick of the Week’ for 12 September 1988 tells us that

Performance art has never had a high profile in Britain, and there has been little cross-fertilisation between the UK and the rest of the world. In a crusade to change this Rob La Frenais, founder of Performance Magazine, has organised Britain’s first international performance art biennale.[1]

This assertion is to some extent wrong in that it elides histories in which UK artists had in fact toured, and were in conversation with international artists in and touring to Britain. However, it does concisely represent valid concerns about a geographically isolated (and historically imperialist) island, and a formal practice of making art which was and continues to be engaged in a struggle against the established or assumed terms of ‘high profile’ art. The event that the article refers to, EDGE 88 (13 – 25 September, 1988) was an art festival with a focus on site-specific performance and installation that took place at various locations around the Clerkenwell area of London.[2] It was organised by the founding editor of Performance Magazine Rob La Frenais,[3] Sara Selwood who was then director of AIR Gallery,[4] and co-ordinated by Alison Ely. Its aim was to ‘bring experimental art to Britain from around the world, in particular live art’ while also ‘exposing and promoting innovative British art, which is currently unfairly isolated through lack of contact with foreign work’.[5] It was designed as an event which was to be closely intertwined and embedded within the local community of Clerkenwell, which had been considered by some a run-down area with many vacated industrial buildings at the time, in the midst of gentrification (a point that I will return to).[6]

Nigel Rolfe, ‘Shooting Shitting’, 1988. Courtesy of AIR Gallery/SPACE archive.

The organisers saw experimental contemporary art, and live art in particular in terms of its potentiality, to counter deadening effects of the art market and its fixed objects, as well as staid institutions and their exclusionary or imperialist bases. A press release from the archive reads:

EDGE 88’s policy is implicit in its title. EDGE 88 and its collaborators believe that the process-based approach of many live and other experimental artists runs counter to the monumental and commodity based approach of traditional artforms, and that this approach knows no physical frontiers, either by media or national boundary.[7]

Indeed, the title EDGE situates the events in terms of innovation (the obvious ‘cutting edge’) and provocation (‘edginess’), but also in complex and not necessarily obvious ways it speaks to the politics of the marginal, the peripheral, or the extreme; it recalls a moment in time which anticipates or is a prelude to a possibility or change which is about to be realised (to be ‘on the edge’ of something); it is a position of precarity (on a knife’s edge); and tense or purposeful energy or movement (to be ‘on edge’, to ‘edge closer’). It speaks to the politics of EDGE 88 as a wilfully shifting point of concentration for itinerant art practices, also shared by other EDGE and related events, including the earlier Art in Danger (Diorama, 1985-86), At the Edge (AIR Gallery, 1987), Last Sweat of Youth (AIR Gallery, 1988), and subsequent events EDGE 89, 90 and 92, until the project’s end after a brief but impactful burst of activity that had taken place in London, Newcastle, Glasgow and Madrid. These events galvanised a set of practices in performance, installation, and otherwise time-based art, and represent a significant focus point in the history of live art in the UK and internationally.[8] It placed a diverse range of artists in conversation with one another: in EDGE 88 artists of the Black British art movement Rasheed Araeen and Mona Hatoum were situated in conversation with artists of colour internationally such as Chinese Canadian Paul Wong; works by feminist artists from the UK such as Helen Chadwick, Rose Garrard, and Tina Keane were placed alongside contributions by European and US artists Ulrike Rosenbach and Carolee Schneemann;[9] performances by Alastair MacLennan and Nigel Rolfe spoke to the urgent politics of the Irish Troubles; while Stuart Brisley, Ian Breakwell, Vera Frenkel, and Zbigniew Warpechowski were among those who represented the dismantling of art’s formal and disciplinary barriers and boundaries that unfolded in the 1970s and beyond.[10] A visitor’s experience of EDGE 88 began with a map and an invitation: to navigate thirteen sites including formerly industrial buildings, a public swimming pool, the cloister garden at the Grand Priory Church of the Order of St John, Finsbury Town Hall, and contemporary art spaces such as the Flaxman and Slaughterhouse galleries (spaces that are now gone), among others. Works in performance, sculpture, and installation were part of a programme which also included a conference and performance-lectures focused on questions of participation and international histories of art, which emphasised the sense in which art unfolds within, between and across discursive as well as physical spaces.[11]

Denis Masi, ‘Screen’, 1988. St James Church, Clerkenwell, London. Courtesy of the Artist

It is a good time to revisit these events, to take stock of the development of live and time-based art, but also the broader questions that EDGE touches on: issues of innovation, diversity, visibility, change, and the politics of place and space, to name a few. Thirty years after EDGE 88, on 4 February 2019 the Edge of an Era event took place at and around St. James Church, Clerkenwell as part of the broader project to document and respond to this history and live art of the 1980s. The project is led by the artist Helena Goldwater, Rob La Frenais, and Alex Eisenberg in collaboration with the Live Art Development Agency. The event began with two walking tours, one of which was led by La Frenais, who narrated EDGE 88 sites around Clerkenwell and remembered the works installed therein. Shortly after embarking on the journey it was clear to the tour group that it would not be straightforward to begin to reconstruct this history, as the majority of the sites had been privatised, built upon, or otherwise closed to public access or viewing. La Frenais commented while looking up at the site of formerly affordable artists’ studios on Clerkenwell Close: ‘artists can’t even afford to buy a pint here [now], let alone have a studio’, and perhaps expectedly the group was asked by a security guard to quickly move away from an area now converted to expensive gated flats. Standing in the street looking in the semi-dark at a high brick wall we nonetheless began to imagine, with Alastair MacLennan’s recollection of the subterranean Clerkenwell Catacombs (a remainder of Middlesex House of Detention), where his performance Bled Edge took place. MacLennan’s piece consisted of a 111 hour installation and performance which was about, MacLennan told us, ‘articulating and accentuating’ the existing aura of the space, where Fenians created a deadly gunpowder explosion in an attempt to free Irish prisoners awaiting trial in the 1860s, and where children had also been held as prisoners. Archival footage of the work shows MacLennan as a shadowy figure moving around a space littered with broken and ghostly objects such as smashed up wood, seemingly abandoned clothes, and British and Irish flags hanging from barbed wire stretching across heavy (and, in a way, sinister) old doors. The proposal for the piece speaks of ‘issues of political, social, cultural alienation and integration’, and MacLennan wrote, ‘When disaster strikes, do we wash the blood, heal the victim, or polish the floor? To heal we make WHOLE’,[12] which recalls – sadly and poignantly – histories of colonial violence, the Irish Troubles of the period, and also the threat to peace posed by Brexit today.

Later, at the Ironmonger Row Swimming Baths we were able to peek in through a newly built viewing window to the pool (in full public use) where Tina Keane’s The Diver took place. The work involved women diving and performing synchronised swimming, lit by a spotlight that followed them around the water that was otherwise in darkness. Footage of the work shows a woman playing a violin, the sound of which echoes around the pool as she floats on the water in an inflatable chair; later, another person dressed in a tuxedo jumps into the water as a deep and rumbling soundscape is heard. These strange and peculiarly ordered images are discordant with the usually very brightly lit and cacophonic space of a public swimming pool, and prompt a re-thinking or re-imagining of space and everyday life. Outside Woodbridge Chapel (Clerkenwell Medical Mission) we were told of Helen Chadwick’s Blood Hyphen, an ‘ambitious’ work of art responding to scientific research, La Frenais said, in which audiences had to climb some stairs and put their heads up into an opening in the ceiling of the chapel, at which point they could see a separate space above which was theatrically animated by a red laser and smoke. Chadwick’s proposal shows that the work was inspired in part by theological scholarship which had interpreted Jesus Christ’s wounds and blood in terms of maternal corporeality, and NHS information pamphlets on smear tests and cervical laser treatment.[13] Extant footage of the work shows the discovery of an alternate world above the chapel ceiling, centred on a previously hidden window drenched in red light to create a fleshy, translucent membrane in a womb-like space. In the archival footage Chadwick’s work contrasts with the bright sunlight and colours of the secret garden where Ulrike Rosenbach swirled around like a Whirling Dervish in her performance In the House of Women, a site which the tour group also caught a glimpse of through a closed gate.

As not only a backdrop, but in a sense an active agent in these works, the environment of Clerkenwell is now known as an area for architects’ offices and luxury furniture design shops; it is one part of vast swathes of the city that have been virtually vacated by communities as privatisation and the cost of living has risen exponentially. The sense of what is or could be possible for art in London has certainly changed, and perhaps in some respects even diminished. Archival photographs show Roberto Taroni in a local classroom preparing for his work Portrait de L’Artiste en Saltimbanque which called for fifteen young children to devise aspects of the performance, and to read a complicated text about ‘theory of dis-architecture’ (the reading of these phrases, which children were unlikely to understand, was pitched to them as a ‘game’) among other things.[14] During the tour Mona Hatoum recounted of her work, Reflections on Value which was installed at 8 Northburgh Street (a formerly industrial building) that she had appropriated found materials nearby which she used as part of her earlier installation Hidden From Prying Eyes (At The Edge, AIR Gallery, 1987), with La Frenais featuring in the story as curator turned getaway van driver. As corporate control over the city has become tighter (evidenced by the criminalisation of squatting and shrinking of public space, for example) it is more difficult to imagine such acts of appropriation being successfully carried out today. Yet, today’s Edge of an Era project is not one which is seeking to nostalgically reconstruct a past history. Rather, it is concerned with the idea of challenging and extending the archive with new acts of creation, connecting past, present and future with a sense of possibility, and with charting ways forwards while also reflecting on works already carried out. With this in mind, Goldwater, La Frenais, Eisenberg and Live Art Development Agency commissioned five emerging artists: Robin Bale, Zvikomborero (Mayfly) Mutyambizi, the collective Something Other (Maddy Costa, Diana Damian Martin and Mary Paterson), Adam Patterson, and Morgan Quaintance to create new works that are somehow in conversation with those of EDGE and its archival representation. Some of this work was represented at the evening of performances and a panel that took place at St James Church after the walking tours.

Walking Salon by Something Other (Mary Patterson and Diana Damian Martin). Part of Edge of an Era event, 2019. Photo: Christa Holka

In her introduction to the evening, Goldwater spoke of the impetus behind Edge of an Era, which was prompted by her frustration that she could not readily find or access materials on performance art events that had been influential to her as an art student in the late 1980s. Later on in the evening, Selwood provided some context for the organisation of EDGE 88, and commented on its demanding responses to ‘raw’ spaces yet to be gentrified, as well as the effects of damaging political changes instituted by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, who had then been in power for almost a decade. La Frenais emphasised historical (and, implicitly, contemporary) concerns about how to create opportunities for international exchange between artists in the face of limiting funding structures; particularly, he addressed the restrictions at the time on the Arts Council funding international work, and that EDGE precipitated or contributed to a change in policy. In his contribution to the panel discussion Alastair MacLennan revisited the function of live art itself, which he characterised in terms of a sense of connection between people as well as times, places and things. These concerns with the formal and political opportunities presented by performance were well represented and responded to in the new commissions. As part of the evening, Something Other (who had also given their own walking tour which explored women artists’ proposals and performance sites) presented work from their Archives of Now, which centred on feminist notions of correspondence between women across time and space. The work culminated in a series of audio letters which speak to (and, in strange ways, from) the women artists of EDGE 88. As the audience were seated, three voices (those of Johanna Linsley, Nisha Ramayya, and Diana Damian Martin) cut across the space from different angles above and around the church pews. They spoke of the fragility of the past as evidenced in the archive, fragmentary and peripheral documents replete with errors, temporal migrations and wanderings, being lost, recalcitrance, and the market’s undue influence on history. The text is comprised of snatches of scenes or ideas such as ‘have you given yourself permission to steal or destroy?’, ‘it’s always hard to be a woman’ (which seems at the crossroads of irony and seriousness), and references to digitally stored records or memories ‘reaching out an invitation, across the warm stretch of time’. Fittingly, the letters begin ‘to you’ and end ‘with love’, which foregrounds their function as correspondence between women, as they reach towards a transgenerational current, conversation, or exchange.

Adam Patterson – ‘Looking for Looking for Langston’, performance. Photo: Christa Holka

Next Adam Patterson, a Barbadian artist based in London and Rotterdam, represented his work Looking for Looking for Langston, which was created in response to Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston, shown at EDGE 89 in Kings Cross in the abandoned wastelands that would become the site for the new Central Saint Martins College of Art, and EDGE 90 in Newcastle. Julien’s piece, which is primarily known as a film work, was inspired by the Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes; as Patterson looked at Julien looking at Hughes, he sustained and extended a thread of connection that spans a century, punctuated by acts of contemplation and desire between black artists. In St. James Church, Patterson walked from behind and through the audience and looked at the screen above which showed a new video rendering of Julien’s Langston on a Caribbean beach. Standing with his back to the audience Patterson wore a white, textured avant-garde costume that was part naval officer, part feathered cockatoo, and part gold glitter bomb. Tiny bells on his tall, fluffy hat tinkled to accentuate moments in a text spoken to the image projected above; Patterson began with a scene of togetherness, eroticism, and fantasy set in a sea shell: ‘We speak and kiss in conch, its inner ear a passage to our “elsewhere”’. Patterson’s figure made for a fantastical and exotic bird which seemed at odds with the tall coldness of the church and its dull colours, perhaps speaking to the exoticisation and Othering of black bodies in cultural and historical institutions in the UK.

Travels and wanderings between times and generations were also marked by Morgan Quaintance, in a video work Anne, Richard & Paul which sutures archival and new footage of Bow Gamelan Ensemble members (who were part of At the Edge, 1987),[15] and Robin Bale who closed the evening with a response to Alastair MacLennan’s EDGE 88 work. In his performance, Invocation, Bale stood on a balcony above and behind the audience, creating a soundscape with a drum, electronic noise, and a spoken text which included statements that destabilise the archive, such as ‘I wasn’t there’ and ‘it never happened’.[16]

Video still from ‘Anne Richard and Paul’, by Morgan Quaintance, 2018